Alphbts ≈ Hrglyphs

As these years pass and digital technology further implants itself into our skin (we are moving from smartphones to smartwatches : computers in our pockets to computers attached to our bodies), English writing is evolving away from phonetic spelling and assuming more logographic spelling.

The casual observer already notices and experiences this with various textisms (omg, ttyl, lol, brb), emoticons, and the l33tsp33k of several internet subcultures. I would like to demonstrate this orthographic evolution with formal linguistic examples. Additionally, I argue that the English spelling system is already heavily logographic. What is written below are just some musings and beginnings of potential explorations.

**

There are four main types of writing: Asemic, Semasiographic, Logographic, and Phonographic.

Asemic writing is wordless writing without semantic content. Not specific to any language, asemic writing is free abstraction that suggests the possibility of semantic content. Styles range from scrawl to calligraphy and beyond.

(more examples of Asemic writing can be found here: http://thenewpostliterate.blogspot.com/)

Semasiographic writing uses glyphs to signify general ideas. These symbols are not dependent to any specific language. Road signs, emojis, and hobo signs are a few examples of semasiographic writing.

Catalog of Hobo Signs

from a flight safety card

Glottographic writing uses glyphs to represent specific language structures. There are two branches of writing under the glottographic umbrella: logographic writing and phonographic writing.

Logographic writing uses glyphs to represent specific ideas (such as “love”) and grammar morphemes (like the subfix –ing in “loving”). Cuniform and Chinese writing are examples of logographic writing. The ampersand (&) is a formal logographic example in English writing.

Babylonian Cuniform

Phonographic writing uses glyphs to represent the sounds of a language. Germanic languages, Romance languages, Semitic languages, languages of India, etc. use phonetic systems. Phonographic writing has further classifications (Syllabic, Segmental, and Featural, but we won’t get into those specifics).

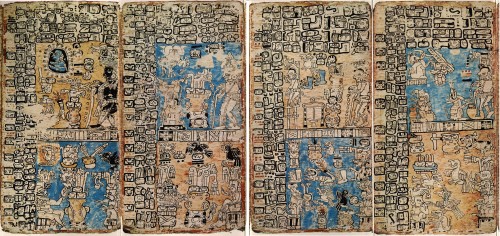

Egyptian hieroglyphs, Maya script and the Japanese writing system are examples that mix logographic and phonographic writing. Sometimes the glyphs are specific ideas and sometimes the glyphs represent sounds to utter.

**

English writing is not as phonetic as we pretend it is. It seems to be moving towards something akin to hieroglyphs.

Example: The word “Right” is a homophone to “Rite”. But, a few centuries ago, “Right” wasn’t a homophone to anything. It was pronounced ReeHt (hard “h” [or rixt in IPA]). Yet we keep the Middle English spelling despite no longer being phonetically similar. A fascination with classical Greek and Roman culture in the 15th and 16th centuries altered the spelling of words to better reflect their etymological roots. “Debt” used to be spelled as “Det”, but a silent “b” was added to reflect that it came from the latin “debitum”.

The centuries that have passed produced a rich vocabulary with countless peculiar quirks in spelling (I before E except after C unless it’s “Weird Science” lol), but this isn’t to say that our spelling system is ridiculous and without reason. English orthography is unique because it showcases etymological elaborations and language cross-pollination (The long E in “Thief” “Pier” and “Achieve” reveal French roots, while “Deer”, “Keep”, and “Tree” reveal Germanic roots). Other European languages, such as Spanish, use strict phonetic writing; a Spanish word is pronounced as it is written, thus it is hard to sink into that words developmental history.

“What irregular spellings tend to do is increase the general visual distinctiveness of words, whether they are homophones or not,” writes Geoffrey Sampson, a scholar in writing systems. A general visual distinctiveness, Sampson argues, renders words quickly and easily recognizable. In terms of reading, we become less dependent on sounding out words in order to understand them and more savvy on recognizing how the words look to determine what it is.

Thus, English writing’s irregular spelling and wide array of possible letter sequences points towards a logographic script. If I spelled a series of words without any vowels after the first letter, you will still be able to read (or, at least, correctly determine) what was written: Ardvrk, Brght, Wtrmln, Flxbl, Knf, Nght. The visual distinctiveness of these words helps us determine what they signify. Of course, there are still many words that depend on the phonographs of vowels: Dp = deep, dip, dope, dupe? Frg = frog, forge?

There have been only a handful of studies examining the relationship between reading and writing cognitive development. English speaking children are more likely to read visually distinct words successfully (such as school, night, brain) but are more likely to misspell them. Likewise, words which are phonologically regular but offer less visual distinction (mat, bat, pin, dip) are more likely to be spelled correctly but read incorrectly. Uta Frith, a psychololinguist, has argued that, for writing systems in general, “the ideal orthography is incompatible with the ideal for reading”.

**

I have barely looked at the implications and functions of English writing in the context of digital technology. There, a harder push towards logographic script is being made with emails, texting, emojis, and hashtags. I was recommended a book regarding the development of writing in the English digital world called “Digital Shift” by Jeff Scheible, so I’m gonna be looking into that next.

These are merely preliminary observations on what I’ve noticed in English writing. I plan on experimenting more with English as a logographic script and play with its possibilities via poetry, (in)formal research, and cataloging anarchist and exploratory abecedariums of children.

There are other perspectives to ponder in the world of writing systems, such as geopolitics and alphabets (The Development of Korean Hangul), the evolution of spiritual thought and alphabets (Hieroglyphs, Alchemy, and Kabbalah), social conditioning and alphabets (spelling bees?), among other weird entry points.